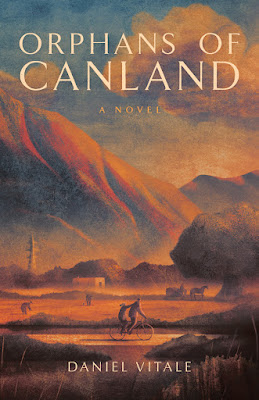

Today it gives the Speculative Fiction Showcase great pleasure to interview Daniel Vitale, whose novel Orphans of Canland was our featured new release on November 16.

Orphans of Canland is your first published novel. What prompted you to write it?

It’s hard to point to one thing. In a broad sense, it was a love for literature and my desire to write. But this story specifically was inspired by the need to engage with subjects that felt meaningful. The fictional world developed through an exploration of climate change and the systemic institutions that perpetuate global warming. And then, perhaps most important for writing a novel, I found a character I wanted to spend more time with: Tristan. His curiosity and optimism required my attention, but I also knew there was something misguided about him. I needed to find out what that was!

Orphans of Canland is set in a far future, but not that far: 2088, when the world has suffered a devastating ecological collapse. What can you tell us about that precipitating event?

The book gives some details about the collapse, or what the characters call the Evanescence—which is to say that nature has suddenly faded out of sight. Basically, it’s the result of all our society’s deleterious practices, so many of which go unregulated in our capitalist, globalized world. Fracking, mass deforestation, careless energy management. And then natural disasters strike. But the question is, how many of those disasters are entirely natural? Aren’t humans partly responsible for hurricanes and wildfires? Helena, Tristan’s mother, and Dylan, his older brother, certainly have thoughts on this…

Your protagonist is a 13-year-old boy, Tristan Weekes. Who is Tristan and what is his situation at the start of the novel?

From the first line of the book, Tristan is a sweet, well-intended boy who doesn’t know his limits. He’s sometimes more capable than he thinks, and sometimes less. In many ways, he’s just a kid. He loves arachnids. He likes to play piano (though Helena prefers him not to). He’s a bit of a budding genius. But the characteristic that defines him in the eyes of everyone around him is his medical condition: analgesia, or, an inability to feel pain. The condition leaves his brain’s stress centers underdeveloped, so he doesn’t know when he’s in danger, or, sometimes, even how he’s supposed to feel. He relies heavily on logic and reason. And while he has what passes for material comforts in this world, he is far from safe.

Tristan lives in the eponymous Canland, a place described as an agrarian California desert-greening project. This sounds benign in itself, but there’s a hint that all is not well. What does the name “Canland” mean and how much can you tell us?

Canland is a portmanteau of the words “California” and “Inland”. The full name for the Part in which the story takes place is “California Inland Valley Desert-Greening Project: a Restoration Part”. So, Canland for short. They’re trying to turn the desert—prone to heat waves, droughts, and geographic isolation—into farmland. Here’s all I’ll give away: they’re mostly successful, but at a cost.

Tristan’s family sounds somewhat dysfunctional. His older brother, Dylan, is a drug-addicted satellite hacker, and his mother, Helena, is described as a “powerful population control-extremist”. His father is absent. How does Tristan relate to his family and what leads him to question his upbringing?

Oof! This is a tough question, since it took me about 350 pages to figure it out! But they are definitely not your ideal, supportive family. Which is not to say they don’t love Tristan, or each other. They do. In fact, their desperation to love and be loved by one another often drives them to do terrible things. They’re full of guilt and sadness and secrets and regret. When Tristan starts defying his limitations, he has to make decisions about how to see the people who raised him, as well as Canland itself, which he has always been so fond of.

When Orphans of Canland opens, the Earth is governed by an eco-totalitarian organization, WORLD. The words “eco” and “totalitarian” are not usually yoked together, but this is a dystopian setting. How has that come to pass?

Exactly! But it is a real-life political-environmental school of thought: to heavily restrict the rights of citizens in the name of environmentalism. In the book, after the Evanescence, this was the guiding philosophy that arose, and so we have a society in which everyone contributes to environmental restoration, but no one (or, I should say, only a few) have certain freedoms we take for granted every day.

This is in part a coming-of-age novel. To what extent did you draw on your own formative years?

I hesitate to say that any of my fiction is autobiographical. Writing is funny like that—everything comes from who I am, but none of it is about me. Does that make sense? I wish I could turn my life into fiction, but whenever I try, it never comes out as interesting as I think it is.

Tristan’s father is a high-ranking member of WORLD who has been absent for two years on a classified research assignment. What leads Tristan to discover his family’s secrets, and the “truths that would suggest his own entanglement with the horrors enacted by Canland and WORLD”?

Unfortunately, this answer would contain ONLY spoilers. So I’ll give the vaguest answer possible, while also trying to compel prospective readers: Tristan’s desire to do what’s right, and the frequent impossibility of knowing what is right, introduces him to people and experiences that provide him a compass toward the truth.

What are the ethical questions at the heart of the novel and what aspects of the present ecological crisis did you want to explore?

What a big and wonderful question! There are too many to list. The one answer that covers both questions, however, is what price we are willing to pay to either destroy or save our environment. What luxuries are we willing to give up? How much are we willing to change the systems in place? Is it even possible? Or, more sinisterly, what species, ecosystems, and even human communities and populations, are we willing to lose in order to stay comfortable and blissfully ignorant?

Tristan has a life-defining medical condition, analgesia, and is also described as “neurodivergent”. How does this affect his ability to navigate the world in which he finds himself?

It’s difficult for Tristan to recognize danger, whether it’s a heatwave or someone being cruel to him. He’s been sheltered by his mother, but he has only love and gratitude for her. But don’t mistake his naivety for shallowness. He has a compulsion to explore, both the exterior world and his own interior world. But it’s hard for him, and he often relies too heavily on the influence of the people around him—which is too bad, because a lot of those people are pretty messed up by the trauma of a worldwide environmental collapse!

A question I keep asking different writers: we live in a dystopian and troubling present. What is the role of dystopian science fiction in these circumstances and how far is hope important?

We sure do. And I’ll be honest, I don’t think that fiction has very much influence on society, not the way it used to. So I think the role of dystopian fiction is to explore—both as a reader and writer—our own outlook on the world. If someone stops to admire a tree, or feel the awe of a landscape, or to watch a bird because of something they read in this book, then that’s enough. Fiction is an experience like any other art, and if it inspires hope, then people can move through the world with a bit more realism and optimism and kindness. That seems like an improvement to me.

Are there writers of Science Fiction and other genres, including literary fiction, who have influenced you when you were growing up?

I didn’t read much as a kid, so I sometimes feel like I’m still growing up, in a literary sense. But now, my bookshelf is full of influences! George Orwell. Kazuo Ishiguro. Margaret Atwood. George Saunders. Octavia E. Butler. Kurt Vonnegut. David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest has so many elements of speculative fiction in it. Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness might be unmatched in the genre of literary sci-fi.

What are you reading now?

Today I am reading All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy. His prose is so rich, I can’t stand it—he makes me think I should just give up writing. And I just finished In the City of Pigs by André Forget, this wonderful Canadian book about a failed avant-garde pianist. Hilarious.

You have written screenplays, poetry, and songs as well as fiction. You spent your first year working in television, and now own a hockey goalie coaching business. Tell us about this and how your job has influenced your writing and Orphans of Canland in particular.

This might sound funny, but writing a 400-page book is way easier for me than any of those other forms of writing. I truly believe I failed at screenplays, poetry, and songwriting because I didn’t have the patience to write something short, like a song or poem, and I felt constrained by the very mathematical screenplay formula. I once wrote a movie that took FOUR HOURS to get through at a table read, and I was like… I need to write books. Now, my goalie coaching job is more of an escape from writing than an informant. But I will say, from the children I’ve coached who have autism, I’ve gained so much perspective on problem-solving, different people’s sense of the physical world, and unlikely senses of humor. All of that made its way into Tristan, in some way or another.

In your author bio, you mention your “interest in the relationship between climate change and the development of the American west”. How has this interest been explored in the writing of Orphans of Canland?

California is such a strange state. It’s like two different states, but it can also be argued that, between Hollywood and Silicon Valley, America goes as California goes. Bear with me as I recite a couple imperfect statistics: two-thirds of California rainfall occurs in the upper third of the state, but two-thirds of water consumption occurs in the bottom one-third of the state. So, there’s a huge imbalance in how this very precious resource is provided and distributed. It makes for a terribly enormous gap in quality of life between social classes. Also, nearly half the food in America is grown in the California Central Valley, which means industry here is always booming, but so is pollution. It’s the most populous state in America, and people are constantly moving here, which means real estate is always developing and overtaking the state’s beauty… I could go on and on. But I’ll end with this: during the gold rush, everyone thought they were going to be the lucky one. Is Hollywood any different? And what about the illusion of the American Dream?

Thank you so much for the wonderful questions, Jessica! I had so much fun answering them, and I hope your readers enjoy this interview.

Thank you!

Thank you for this insight into Vitale. I read the book and thoroughly enjoyed it and fell in love with Tristan. Vitale seems equally interesting and lovable as well.

ReplyDelete