The truth, unfortunately, is a big fat NO.

A little history

Let's look at some examples of European swords from 1000-1500 AD.

| Here are some German zweihanders, which were probably the biggest swords to be used on the battlefield. |

|

| Here's a Swiss longsword, which was commonly used in two hands. |

|

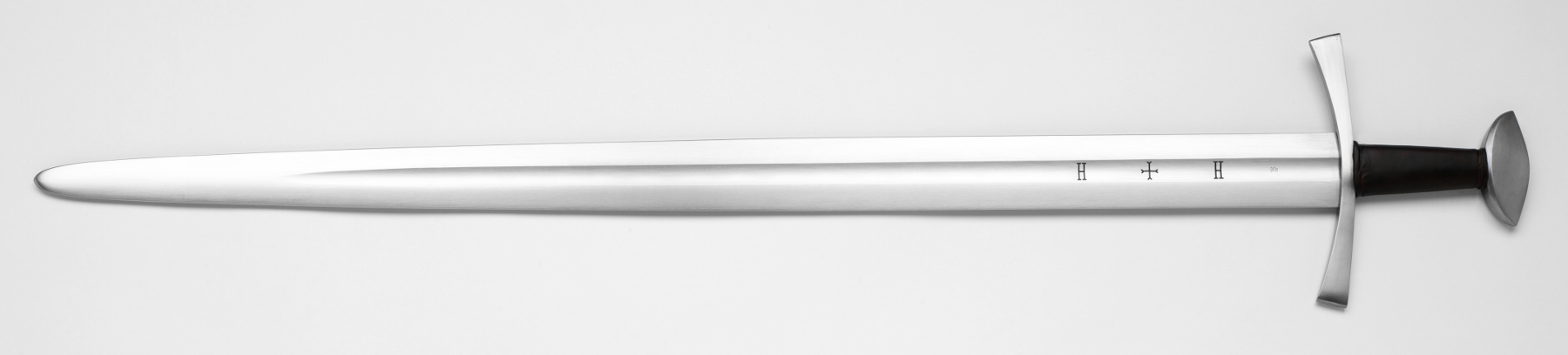

| This one is a replica of a 13th century arming sword, which would have been used in one hand along with a shield. |

|

| And finally, a selection of rapiers, daggers, and basket-hilt broadswords. |

Now, I'm sure the first thing you'll notice is that these swords look rather boring. They're all quite long and thin, with no unnecessary spikes or bits added on. It might surprise you to learn that all of them, even the zweihanders, are very light, even deceptively so. Usually, the first thing that a newcomer to HEMA says on being handed a longsword, for example, is 'Wow, it hardly weighs anything!'

Those medieval weaponsmiths did not mess about, believe me. Their blades were made from high quality steel, and so of course they were light and strong. The idea of a giant, unwieldy sword that no one but a strong champion can lift is pure Hollywood fantasy. A real sword doesn't require a lot of strength to move it effectively through space.

The physics of swordplay

So, you need a certain amount of strength to swing a sword. It's far more important, however, that you have the strength to stop it mid-swing and change direction. Up to a point, there comes a trade-off between the power of a blow and how much you can do once the blow is in motion. Swing too hard, and you are very, very dead when your opponent parries and you can't stop the counter-attack.

But would you ever want to swing particularly hard? Well, no, not really. The big, obvious wind-up, as a hero grunts with effort, is another Hollywood fantasy. Likewise the idea of swordplay being slow - most movies show swordplay that is actually as slow and frustrating as watching a Formula 1 car driving through a parking lot! If you connect with a blow, it doesn't take much to do a lot of damage against an unarmoured opponent. A rapier, for example, only needs about 4lbs of force to skewer someone. Swinging a sword is really not like swinging a baseball bat, regardless of what you see in the movies. Fencing, even with really big swords, is all about precision, speed, skill, and muscle memory rather than strength.

This brings me on to talking about the crossing of the swords. This is a very important concept in swordplay, and it's the big reason why strength is so much less important.

Who would win in a fight?

The answer is Inigo, every time.

Time for a quick lesson on HEMA! Here's a breakdown of the various parts of the sword, using a rapier for reference:

- Crossing over the centre line between you and them

- Putting your sword's forte (the part near the hilt where you can apply a lot of force) against their sword's debole (the part far away from the hilt where very little force can be applied)

- By keeping your true edge (on the same side as your fingers) on top of their false edge (on the other side from their fingers)

Swords behave very much like long steel levers, so these three elements combine to negate your opponent's strength and enhance your own. Gaining a good crossing is so effective that it honestly doesn't matter how much bigger and stronger your opponent is. Unless they're also skilled enough and precise enough to gain the crossing back, they'll be the one bleeding out at the end of the fight. (In my HEMA club, there's a very common demonstration which shows the power of a good crossing. The instructor places the biggest new fighter against the smallest one, and has them cross swords while giving the latter the three advantages above. Then they tell the former to try to move their sword. Every time, the sword cannot be moved, no matter how much force the fighter puts into it.)

In the fight between Inigo and the Mountain, Inigo could likely put the light, thin rapier blade through the other man's eye socket three times before he could swing once. But even if the Mountain did swing his big, heavy sword with all his might, Inigo only needs enough skill to catch the blade on a good crossing, and suddenly all that strength counts for nothing.

HEMA practitioners generally act on the assumption that real swords look a particular way and swordfighters learned a particular way because that was what worked. I think it's clear that strength is the least important attribute in medieval swordplay simply because it's the only one where you don't need more of it to win a fight. Against a fast, skilled, precise opponent, you need to be faster, more skilled, and more precise - but against a stronger opponent, all you need is to know the right technique.

About Claire Ryan:

Claire Ryan is a writer who produces fantasy adventure, steampunk, sci-fi, genre - basically anything weird. She's worked in online advertising, affiliate marketing, and (gasp) retail management, and she's finally decided to try writing books for a living.

She wrote The Author's Marketing Handbook because she got tired of repeating herself all the time while talking to other writers.

Her first novel is due out summer 2015.

== Irish ex-pat now living the Canadian Dream in Vancouver. Web programmer by day. Occasional maker of cloth-based stuff. Book-binder. Longsword fighter. ==

She wrote The Author's Marketing Handbook because she got tired of repeating herself all the time while talking to other writers.

Her first novel is due out summer 2015.

== Irish ex-pat now living the Canadian Dream in Vancouver. Web programmer by day. Occasional maker of cloth-based stuff. Book-binder. Longsword fighter. ==

No comments:

Post a Comment